Government internet shutdowns around the world are insidious, isolating and on the rise.

On Oct. 1, the Iraqi government pulled the plug on the country’s internet. With no warning, out it went like a light. Ever since, the internet, messaging services and social networks have flickered on and off like faulty bulbs.

This is far from the first internet shutdown Iraq has suffered. But according to Hayder Hamzoz, CEO and founder of the Iraqi Network for Social Media, not since 2003 and the regime of Saddam Hussein has internet censorship been so severe.

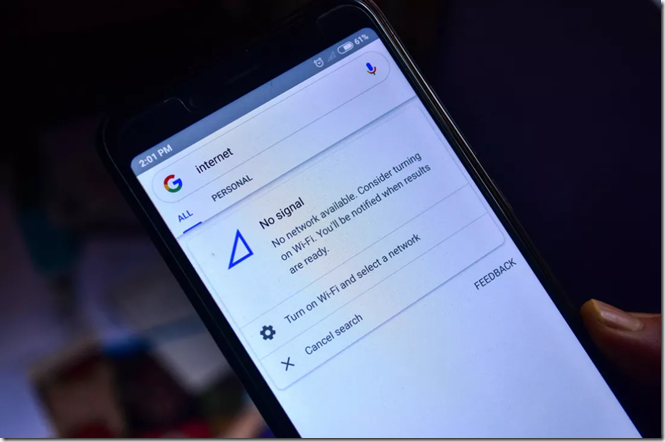

In this age of reliance on internet connectivity, the idea of suddenly flicking connectivity off like a switch sounds dystopian. But for many people around the world, it’s increasingly becoming a reality. They might not even realize it’s happening until too late.

First the signal disappears from your phone, so you restart it, take the SIM card out and put it back in again. No joy, so you try the Wi-Fi, but that doesn’t work either. Maybe it’s a power outage, you think, but your other appliances are working so that can’t be right. You read a news story in the paper about a political protest that’s taking place, and it suddenly becomes apparent that it’s not just you. The government, worried about the protest, has decided to turn off the internet.

This is exactly what happened to Berhan Taye the first time she experienced an internet shutdown, while visiting family in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2016. Since then, she says, it has become “definitely something that I’ve experienced one too many times.”

Taye leads the nonprofit Access Now’s Keep It On campaign, advocating against internet shutdowns around the world. Around 200 partner organizations work with the campaign to prevent intentional shutdowns of the internet by governments around the globe, a form of repression that the United Nations unequivocally condemned in 2016 as a violation of human rights.

Iraq has seen mass civilian protests over the past year, leading to internet shutdowns.

Picture Alliance/Getty

Authoritarian governments have long sought control over their subject populations, and internet shutdowns can be seen as a digital extension of traditional censorship and repression, notes Taye.

This is very much the case in Iraq, where anti-corruption protests that sparked the shutdown are also being combatted with curfews and violence from security forces. Over WhatsApp, Hamzoz described the violence he had witnessed in Iraq during blackouts — tear gas, hot-water cannons, live bullets and snipers.

“It sounds terrifying,” I said. “Very terrifying,” he agreed.

India: Disconnected

In 2018 there were 196 documented internet shutdowns across 25 countries, primarily in Asia and Africa, according to a report released by the Keep It On coalition. Since the Arab Spring of 2011, when censorship ran rife across North Africa and the Middle East, internet shutdowns have been widely associated with authoritarian regimes.

But the country leading the way isn’t authoritarian, or even semi-authoritarian. In fact, it’s the world’s largest democracy. Of those 196 shutdowns that happened last year, 134 took place in India. The primary target is the state of Jammu and Kashmir, a politically unstable region on the border with Pakistan.

In August, the Indian government approved changes revoking the autonomy of the Muslim-majority region, stripping it of its constitution and imposing “security measures” that prevent freedom of movement, public assembly and protest. The region will be split into two territories governed by individual leaders who will report to the Hindu-led government in New Delhi, it was announced Wednesday.

Kashmir has been without internet since the constitutional changes in August, with phone signals also dropping out intermittently.

“This blackout has pushed the entire [8 million] population of Kashmir into a black hole, where the world is unable to know what is happening inside a cage and vice-versa,” said Aakash Hassan, Kashmir correspondent at CNN-News18.

The contested region of Kashmir has been on lockdown since early August. Internet has been shut down for much of that time.

Ahmad Al-Rubaye/Getty

The situation for journalists “couldn’t be worse,” Hassan told me. Everything from sourcing to fact-checking to filing stories often grinds to a halt. He knows of reporters trying to operate in these conditions who have been questioned, injured or detained by the authorities, while also being prevented from speaking out about what’s happening to them.

But Hassan also knows first hand of the toll internet shutdowns can take on people’s personal lives and relationships. During the recent shutdown his grandmother passed away. It took him 14 hours to learn of her ill health, by which point he had missed his chance to say goodbye.

“I was just one hour away from my home,” he said. “But due to the communication blackout, I couldn’t see her face for the last time.”

Most of India’s internet shutdowns are ordered at the regional government level, although it’s often hard to tell where the orders come from. Legally, it’s hard to fight shutdowns, although there are often attempts to do so. For a start, governments rarely acknowledge that internet shutdowns have taken place. When they do, they often give ambiguous reasons for their actions.

For the public good?

The Keep It On campaign tries to map the justifications governments give for shutting the internet down against the actual causes. The most frequently used reason is “public safety,” but in reality this is a broad church that can mean anything from public protest to communal violence to elections.

Jan Rydzak, a research scholar at the Stanford Global Digital Policy Incubator, has been monitoring shutdowns in Kashmir for some years. If public safety is the real priority, he says, shutting down the internet is unlikely to make much difference. In February 2019, Rydzak published a paper demonstrating that shutdowns didn’t discourage or prevent violent protests from taking place.

“Public safety is always a convenient excuse,” he said, “because in the vast majority of the cases it is written into the law of a given country that in situations of public emergency or public safety concerns, the government has special powers to, for example, cut off communication.”

Public safety is indeed the excuse that has been used in this most recent shutdown in Kashmir, which Rydzak describes as a “digital siege.” This excuse is plausible in line with the levels of violence the long-contested region has witnessed, but according to Rydzak, there are ulterior motives.

“They’re looking basically for something that would extend their control over the territory to the greatest extent possible,” he said. The Indian government doesn’t know what will work, he explained, which has led to it “crudely cutting off all contact with the outside world.”

Attempting to use the internet in Kashmir has been fruitless for much of the last three months.

SOPA

There are many reasons why they shouldn’t, starting with Rydzak’s own research in India, which shows empirically that shutting off internet access does not reduce violent protests, and sometimes even perpetuates them.

As an ascendant power, Rydzak adds, the frequency with which India is shutting down the internet is setting a bad example for other countries. Seeing shutdowns as another tool in their arsenal for tackling outbreaks of violence or protests, more and more countries are experimenting with shutting off the internet just to see how it goes, he said.

This is echoed by Keep It On’s research, which shows an escalation in the number of new countries opting to use shutdowns for the first time, according to Taye. Often they do so around the time of elections — a trend that has increased over the past year, starting with Bangladesh at the end of 2018, followed by the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Benin.

“From 2018 I can list 10 countries that did not shut down the internet, but this year they are the frequent culprits of shutdowns,” she said. “Benin is a fairly democratic country. I never would have assumed they would have shut down the internet, but they did.”

Now aware that elections might result in shutdowns, the Keep It On campaign is keeping a particularly close eye on countries where elections are imminent to monitor for disruption.

From shutdowns to slowdowns

Measuring shutdowns is important to know where the rights are being violated, but keeping track isn’t always easy. Telecoms infrastructure is poor in many countries where shutdowns take place, so a steady internet connection isn’t something that can be relied on at the best of times.

“It’s very difficult for a lot of people to figure out if it’s an intentional shutdown, or if it’s just a fiber cut, or if your internet is just having a bad day,” said Taye.

This is further confused by the fact that many governments use less obvious, more insidious tactics in hyperlocal shutdowns or slowdowns. Often they’ll target specific social media services for throttling, or slowing down the bandwidth. WhatsApp, widely used in developing countries due to its low data costs, and Facebook are regular targets.

Either governments can make the services unavailable altogether, or can make them painfully slow to use. Some of these slowdowns are designed specifically to stop people being able to send pictures and videos, which would be more likely to inflame tensions or serve as evidence.

“We are deeply concerned by the trend in some regions and countries towards shutting down, throttling, or otherwise disrupting access to the open internet,” said a spokeswoman for Facebook. The company offers training to governments and law enforcement to help them address emerging situations by maintaining their own online presence and combating the spread of misinformation with appropriate counter speech.

Another justification used by governments to shut down internet access is to stop the spread of misinformation. Following the Easter bombings that took place in Sri Lanka earlier this year, for instance, some Western media were quick to praise the government’s decision to block access to social media to prevent the spread of false information.

The Easter bombings in Sri Lanka led to the government blocking social media for the purpose of curbing the spread of misinformation.

Lakruwan Wanniarachchi/Getty

But it did no such thing. Just as shutdowns in Kashmir didn’t stop political violence, misinformation ran rife and even ended up in the coverage of major international news outlets. A Brown University student was at one point falsely identified as the attacker.

Blocking social media doesn’t prevent the spread of false information, according to Keep It On. It simply delays it. Taye gives an example, again from Ethiopia, where in July this year the government shut down the internet for a week following a series of assassinations of important political figures.

“When they turned on the internet, all of the conspiracy theories, all of the craziness that was happening in the offline space did not stop,” she said. It was all still there, just pending, waiting for people to be reconnected so it could continue to spread.

In the meantime, the last information put out before a shutdown often becomes the dominant narrative — whether or not it’s accurate.

As for the social media blockage in Sri Lanka, it wasn’t only unsuccessful at preventing the spread of fake news, Yudhanjaya Wijeratne of the LIRNEasia think tank wrote in a Slate op-ed following the bombing. It also prevented people from getting in touch with one another to report their safety, and it hid the inability of the police to control violent protests — which were partially caused due to the spread of misinformation.

Living in the dark

As if the lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of blackouts wasn’t enough to dissuade countries from deploying them, the economic toll of shutting off the internet can also run to millions of dollars per day.

According to a study conducted by Deloitte for Facebook in 2016, shutdowns can cost high-connectivity countries up to 1.9% of their GDP per day. Shutdowns in India are estimated to have cost the country over $3 billion since 2012, according to a report published by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations last year.

But they also have a trickle-down effect that takes a huge toll on the livelihoods of individuals who over the past 10 years have come to rely on the internet for their income. “Behind every figure like that are dozens of businesses that went out of business,” said Rydzak.

In Iraq, Hamzoz said, tech startups and local Uber rivals providing taxi-hailing services are losing out daily without steady access to the internet for themselves or their customers. Startups are going out of business. Women who rely on taxi-hailing apps for safety reasons must either stay home or risk their safety.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo’s government is one of many to employ internet shutdowns for the first time in the past 12 months.

Federico Scoppa/Stringer

Similarly in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, internet access has allowed the informal economy, which women and other marginalized groups rely on for an income, to thrive. When people live in remote places or don’t have access to physical premises, business is often conducted through WhatsApp or Facebook groups and relies on digital payments.

According to Ashnah Kalemera, programs officer at Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa, this extends to all manner of casual work, including the buying and selling of food, laundry and hairdressing services.

“Many women are running businesses in this informal economy set up to ensure financial security,” she said. “Let’s not forget that African women are still largely excluded from the funds afforded to their male counterparts for formal tech startups.”

If the internet goes down, income streams are abruptly interrupted. For some women this means suddenly not being able to afford to feed their families, to send their children to school and to access other basic necessities.

Enterprising people have found ways to get around shutdowns — the use of VPNs to access social media is widespread. In a total blackout, however, these are also often rendered ineffective. In Iraq, Hamzoz told me, some people use international SIM cards, but they are expensive and the signal is often weak.

As we spoke over the course of October, when protests over corruption and poor living standards in Iraq raged on, Hamzoz reported the ongoing flickering status of his country’s internet and social media outages. On Oct. 16 he said mobile internet was partially restored. Then on Oct. 25, when mass protests broke out, it went down again. At the time of publishing, Iraq has largely been without internet for almost an entire month. Hamzoz said he expected blackouts and slowdowns to continue until the political issues in the country are addressed.

For Iraq, just like Kashmir, Jammu, Ethiopia and many other places around the world, that means internet shutdowns are likely to be a fact of life for the foreseeable future.

Start now to make sure you are staying prepared.

via: cnet

Follow

Follow